By Risa Pieters

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Disaster Risk Reduction Education

2.2. Affective Learning

3. Affective Learning in Disaster Risk Reduction Education

4. Challenges

5. Conclusion

6. References

7. About the Author

1. Introduction

“We need to keep our children safe and to involve them directly in our work to strengthen disaster preparedness.”

- UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, 11 October 2006

While nations made significant strides in reducing poverty and working towards the Millennium Development Goals by 2015, disasters reeled back years of development and progress. As seen in one year alone, 2011, 302 natural hazards resulted in disasters that caused damages worth an estimated US$366 billion (UNISDR, 2012). In that same year, disasters killed almost 30,000 people and affected about 206 million people, illuminating the urgent need for enhanced disaster risk reduction not only to safeguard progress but also to ensure basic human rights for all (UNISDR, 2012). Now, as nations work toward the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, disaster risk reduction (DRR) education will be pivotal in achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 and recent disasters such as Hurricane Harvey (Texas, United States) in 2017, unveiled the destruction that can ensue across social, economic, and political dimensions and starkly reminded the world that even developed nations are not immune to natural hazards. The incorporation of disaster risk reduction education in school curricula is critical for all nations as DRR education helps develop more resilient communities through raising responsive citizens across all sectors. The success of DRR education in enhancing motivation and guiding pro-social action however relies upon the ancillary internalization of values and responsibility in addition to environmental knowledge and awareness. This entry explores the potential of incorporating affective learning into DRR education to facilitate the internalization of moral values that motivate individual and collective change in behavior.

2. Background

2.1. Disaster Risk Reduction Education

UNESCO/UNEP, 2011, p. 63.

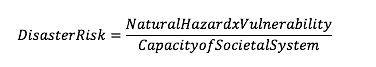

Natural hazards are an innate part of nature; however, human alterations to the natural environment such as rapid urbanization and environmental degradation, inter alia, increase risk and pave the way for hazards to amass into disasters (Hidajat, 2009). A societal system’s capacity to mitigate the extent to which a natural hazard exacerbates into a disaster rests upon socio-economic determinants such as access to information and financial capital (UNESCO/UNEP, 2011). Consequently, developing countries and vulnerable populations suffer a disproportionately higher disaster risk.

Disaster risk reduction requires a collaborative approach across all sectors, thus DRR education is fundamental in equipping individuals and communities with the information and capabilities needed to reduce vulnerabilities in different contexts. A more comprehensive definition of DRR education is delineated by Selby and Kagawa (2012, p. 29) in their UNICEF/UNESCO report on DRR education in school curricula:

Disaster risk reduction education is about building students’ understanding of the causes, nature and effects of hazards while also fostering a range of competencies and skills to enable them to contribute proactively to the prevention and mitigation of disaster. Knowledge and skills in turn need to be informed by a framework of attitudes, dispositions and values that propel them to act pro-socially, responsibly and responsively when their families and communities are threatened.

DRR education has been strongly supported by governments and international organizations and the integration of DRR education in school curricula was marked as an indicator of achievement after the 2005 World Conference on Disaster Reduction. 168 UN Member States adopted the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters, and agreed to ‘use knowledge, innovation and education to build a culture of safety at all levels’ (UNISDR, 2005, p. 9). The inclusion of DRR education in curricula was further endorsed by the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) campaign in 2005, Disaster Risk Reduction Begins at School. Succeeding the decade guided by the HFA, TheSendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 was adopted at the third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction and endorsed by the UN General Assembly to provide a comprehensive DRR development agenda.

2.2. Affective Learning

Within the domains of learning, affective learning incorporates emotions, attitudes, motivations, and values into the learning process to encourage students to translate information and awareness into impactful behavior. In engaging the affective domain, this style of learning encourages internalization, a process in which a student’s affect towards a subject like disaster risk reduction builds upon general awareness and serves to change or guide student’s values and behavior (Seels and Glasgow, 1990). Affective learning in DRR education may take the form of storytelling, sharing hopes and fears around hazards and disasters, debriefing emotional responses to experiences, or empathetic exercises (UNISDR, 2012). Research suggests that affective learning results in enhanced personal growth and behavior change in addition to conceptual understanding (Bolkan, 2014).

The empathetic practices of affective learning also assist in unveiling the vicissitude of fortune and the exigency of individual and collective efforts to reduce that felt risk. Integrating these practices with intellectual stimulation drives motivation by fostering greater awareness of one’s capabilities and impacts (Deci et al., 2001). Affective learning thus enhances curricula, beyond rote environmental science knowledge, by facilitating the internalization of values and responsibility to motivate students to act pro-socially.

3. Affective Learning in Disaster Risk Reduction Education

UNESCO and UNICEF in 2012 jointly published a report by Selby and Kagawa, which was the primary output of a 2011 co-joint Mapping of Global DRR Integration in Education Curricula consultancy.Data were collected from thirty countries and presented with technical guidance for optimal DRR integration and practice in schools. The DRR curricula examined in the study show engagement through different learning modalities: interactive learning, affective learning, inquiry learning, surrogate experiential learning, field experiential learning, and action learning (Selby and Kagawa, 2012). A leitmotif of the curriculum review is the lack of comprehensive and interdisciplinary approaches in DRR education in school curricula (UNISDR, 2005). DRR education is noted to be primarily integrated into school curricula within the natural sciences, largely focusing on the environmental science of natural hazards and response procedures (UNISDR, 2012). Integration, however, should be comprehensive in linking disaster risk across social, economic, and political dimensions as disaster risk reduction requires a collaborative effort from all sectors. Exclusively teaching natural disasters through an environmental and emergency response framework diverts attention from prevention and mitigation, conveying the inevitability of natural disasters and rendering nugatory change in behavior (Selby and Kagawa, 2012).

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reductionsimilarly stresses the importance of pedagogical approaches that promote action and equip students for decision-making with interdisciplinary, analytical, and emotional knowledge (UNISDR, 2015). The integration of affective learning can help achieve this as it develops emotional intelligence, which is critical in motivating individuals to act pro-socially to reduce their community’s risk. Although emotions associated with disasters can be distressing and traumatizing, they constitute a powerful pedagogical tool and should not be disparaged. Through affective learning, students can participate in empathetic exercises exploring past hazards and engage in imaginative learning to relate impacts to their own lives. Encouraging students to engage with emotions related to disasters can shift their attitudes, dispositions, and values, and ultimately motivate them to act in future unforeseen events and circumstances. Incorporating affective learning also aids in shifting outlook and behavior by acquainting students with the vicissitude of fortune, raising awareness that any of those victims could have been given a change of circumstance and the limited predictability of natural hazards (Coeckelbergh, 2007). Affective learning practices, such as exploring personal stories, news coverage, interviews, and photographs, allow students to engage with the emotional and innately human aspects of disasters. This, in turn, helps make a stronger connection between the importance of risk reduction and responsibility across social, economic, and political realms.

Other practices employed in affective learning, such as visualizing outcomes, also foster higher emotional engagement. Imagination-driven social emotions discovered through affective learning can guide future decisions and actions as moral emotions are precursors of moral thoughts and behavior change (Kind and Kung, 2016). For example, engaging with positive affect states can support a student’s evaluation of choices. Stories about actions that lead to moral appraisal have shown to be motivating for students; positive emotions associated with inspiring change-making individuals and communities can build self-esteem and confidence in taking action (Kind and Kung, 2016). A high correlation has been drawn between personal self-worth and level of altruism and motivation to take action for the good of the community (Selby and Kagawa, 2012). Affective learning can facilitate this connection between emotional engagement and motivation for pro-social action to enhance DRR education’s impact beyond transfer of knowledge.

Given the emotional intelligence value-add of affective learning, the paucity of this approach in DRR curricula is disconcerting. In the findings of Mapping of Global DRR Integration in Education Curriculaonly three countries – Fiji, Malawi, and New Zealand – employed DRR education through an affective learning mode of curriculum (UNISDR, 2012). This highlights the shortfall of most DRR education in school curricula in giving little weight to skills and attitudes and primarily focusing on knowledge and awareness (UNISDR, 2012). The learning outcomes of affective learning – the internalization of values and responsibility – align with the aim of DRR education to build the capabilities of students to act pro-socially. Thus, there is strong reason to incorporate affective learning practices within DRR education in school curricula to grow responsive and responsible citizens and ultimately build resilient communities.

4. Challenges

A challenge in integrating affective learning into DRR education is that it requires significant teacher training in facilitating emotion and trauma simulated learning. Affective learning practices and imaginative learning can be unfamiliar or uncomfortable for teachers accustomed to a textbook culture, thus it may require further teacher training and support. Additionally, since natural hazards are increasing in frequency, more students are learning about disaster risk reduction after experiencing a disaster. Teachers may need to be cognizant of the need for psychosocial support for students who may be suffering from trauma while engaging in affective learning (UNISDR, 2012). An additional challenge arises with monitoring and measurement of the correlation between shifts in values and attitudes and reduction of disaster risk. Due to DRR education’s future-oriented nature, outcomes are also classified as decisions made in future unforeseen events and circumstances, thus rendering monitoring and measurement of success to be limited. Lastly, a challenge may be posed by the contentious nature of climate change. While some countries such as Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Benin, and Nigeria have incorporated climate change as a primary lesson in DRR curriculum, many schools avoid the topic due to its political and controversial nature (UNISDR, 2012). Although it is widely agreed upon that climate change is exacerbating the frequency and intensity of disasters, whether climate change is natural or caused by humans is still a highly debated topic. Thus, the implementation of affective learning to shift behaviors, attitudes, and values may be considered too political and can result in disagreement.

5. Conclusion

Since 1981, the increase of natural disasters in number and magnitude has caused severe economic loss, the extent of which is higher than GDP growth per capita in OECD countries (UNISDR, 2011). The risk of losing wealth and reversing economic progress due to natural disasters is now exceeding the rate at which the wealth itself is being created; therefore, disaster risk reduction is and will continue to be critical for sustainable development (UNISDR, 2011). The economic, social, and financial costs of disasters not only impede growth but also reel back years of development as infrastructure is destroyed, education is disrupted, and physical and psychological trauma ensue. Disaster risk is evidently a human rights issue as it infringes upon the right to live and develop healthily (UNICEF, 2011). The mitigation of disaster risk requires a collaborative effort and it begins with the empowerment of children, encouraging them to change in behavior and to contribute as responsible citizens to the resilience of the larger community over time. For disaster risk reduction education to succeed in its purpose of informing students with a framework of attitudes, dispositions and values that propel them to act pro-socially, learning must go beyond the transfer of rote environmental science knowledge and work to build capabilities and emotional intelligence. Thus, integrating affective learning into DRR education, to promote the internalization of moral values and to motivate pro-social action, will be pertinent to attaining the 2030 sustainable development agenda and building a more resilient future.

6. References

Bolkan, S. (2014). Intellectually Stimulating Students’ Intrinsic Motivation: The Mediating Influence of Affective Learning and Student Engagement. Communication Reports. 28(2). doi: 10.1080/08934215.2014.962752

Coeckelbergh, M. (2007). Imagination and Principles: An Essay on the Role of Imagination in Moral Reasoning.Palgrave Macmillan.

Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, and Ryan. (2001). Motivation and Education: The Self-Determination Perspective. Educational Psychologist. 26(3-4). doi:10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

Hidajat, R. (2009). World Conference on Education for Sustainable Development. Concept Note: Learning to Live with Risk – Disaster Risk Reduction to Encourage for Sustainable Development.German Committee for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Kind, A & Kung, P. (2016). Knowledge Through Imagination.Oxford University Press.

Oskin, B. (2017). Japan Earthquake & Tsunami of 2011: Facts and Information. LiveScience.

Seels, B. & Glasgow, Z. (1990). Exercises in Instructional Design.Merrill Publishing Company.

Selby, D. & Kagawa, F. (2012). Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula: Case Studies from Thirty Countries. United Nations Children’s Fund.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (UNICEF). (2011). Disaster Risk Reduction and Education. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/environment/files/DRRandEDbrochure.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)/United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2011). Climate Change Starter’s Guidebook: An Issues Guide for Education Planners and Practitioners. Paris: UNESCO/UNEP.

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. (UNISDR). (2005). Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Geneva: The Author.

UNISDR. (2012). Towards a Post-2015 Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Retrieved from http://www.unisdr.org/files/25129_towardsapost2015frameworkfordisaste.pdf

UNISDR. (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Retrieved from http://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf

About the Author

Risa Pieters

MEd, The University of Hong Kong

Email: risa.pieters18@gmail.com