By Luo Yu

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background: Sleep Disorders

3. Sleep Problems among Adolescent Students in Hong Kong

4. Sleep Education as a Solution

5. Recommendations for Sleep Education in Hong Kong

6. Conclusion

7. References

8. Key Terms and Definitions

9. About the Author

1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, set up 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Promotion of mental health and well-being is one of the targets outlined in Goal 3. Psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression, can lead to suicide. Suicide is reported as the second leading cause of death among young people in the 15-29 age group (United Nations, 2016). Studies have shown that long-term sleep problems are positively associated with such psychological problems (Adrien, 2002; Breslau et al.,1996; Richdale, 1999). However, sleep problems are often overlooked by people.

Students in Hong Kong bear a heavy academic burden which may result in sleep problems (Chung & Cheung, 2008). Even though many adolescent students suffer from sleep disturbance, sleep education in Hong Kong only started recently, and various difficulties have been encountered in launching such educational programs. Although sleep education provides adolescents with knowledge about sleep, few consistent outcomes have been observed in improving sleep after sleep education programs (Chan, 2016). The effect of sleep education remains unclear.

This entry begins by explaining different forms of sleep disorder. It then discusses the factors that affect sleep and the current situation of sleep problems among Hong Kong adolescent students. After that, sleep education as a possible solution, and its function and effectiveness in a global context and in Hong Kong, are examined.

2. Background: Sleep Disorders

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, there are three main types of sleep disorders (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014) and they include:

- Insomnia

Insomnia, also called sleeplessness, is typically characterized by difficulty in initiating and/or maintaining sleep. Usually, people who suffer from insomnia also wake too early and cannot get insufficient amounts of nocturnal sleep.

- Sleep-Related Breathing Disorder

Dysfunctional sleep breathing is the characteristic feature of sleep-related breathing disorder. Obstructive sleep apnea, the most common type of this disorder, causes inadequate breathing during sleep. Snoring is often seen as a symptom of this disorder.

- Parasomnia

Parasomnia involves abnormal movements, behavior, emotions, perceptions, and dreams that accompany sleep. Sleepwalking and teeth grinding, for example, belong to this kind of sleep disorder.

3. Sleep Problems among Adolescent Students in Hong Kong

Sleep is a complicated activity that interplays with environmental, physiological and psychological factors. Though the relationship between many sleep-related behaviors and sleep quality remain ambiguous and some factors are in common (e.g. age, gender, family communication, etc.) in adolescents all over the world, there are significant external factors which are relevant to Hong Kong youth.

People spend almost one-third of their lifetime in sleeping. Adolescents, at their transitional stage of physical and psychological development, need more sleep than adults. Nevertheless, sleep deprivation is prevalent among adolescent students in Hong Kong. An epidemiological study has pointed out that the average sleep time among 1629 Hong Kong secondary school students was only 7.3 hours during school nights (Chung & Cheung, 2008), less than the 8 to 9 hours which is commonly suggested for adolescents (National Sleep Foundation, 2000). From 2006 to 2008, the Hong Kong Student Obesity Surveillance (HKSOS) project investigated 22,678 Chinese adolescent students aged 12 to 18 on sociodemographic characteristics, sleep patterns and problems etc. As it demonstrated, only 27.4% of the participants slept more than 8 hours on school nights. Most insomnia disorders involved difficulty in initiating sleep (12.3%), followed by difficulty in maintaining sleep (8.8%) and early morning awakening (7.2%) in the case of participating students (Mak et al., 2012). Another investigation completed by 529 Hong Kong college students indicated that 68.6% of the participants were insomniacs (Sing and Wong, 2010). Accordingly, insomnia is very common among Hong Kong students.

Academic Stress is a major factor in adolescent sleep disorders in Hong Kong. Recent decades have witnessed an increasing academic load for adolescent students (Bjorkman, 2007; Kaplan et al., 2005). Chung and Cheung’s (2008, p. 193) study shows ‘that high perceived stress was the most significant risk factor for sleep disturbance among secondary school students in Hong Kong’. They also discovered that students who have marginal academic performance usually sleep less during the school week than students with better grades. Student in different stages of their studies also demonstrate different sleep quality norms because each study year may have various academic and life pressures. For example, university students in the first and the third years of study are reported to have more sleep problems (Suen et al., 2008).

Academic pressure is not only one major significant risk factor for sleep disorder among adolescent students, it also has an impact on students’ psychological health, as it causes anxiety and depression. Sleep problems exacerbate these mental disorders, and anxiety and depression lead to poorer sleep quality and thus academic performance. Each of these is in an interrelated web of relationship (see Figure 1.).

Figure 1 Relationship between Sleep Problem, Academic Pressure, and Mental Disorders

As a preventative measure, sleep hygiene practice includes different actions that can be taken before sleep or during the daytime to enhance sleep health. Such actions as night eating, drinking alcohol, beverage containing caffeine or dairy product, taking naps during the daytime, performing active exercise, and using electronic devices before sleep may all lead to poorer sleep quality and even insomnia. A survey conducted with 400 university students in Hong Kong found that students who self-reported to have poorer sleep quality got significant lower average scores in sleep hygiene practice assessments (Suen et al., 2008).

4. Sleep Education as a Solution

Education can raise awareness and disseminate knowledge about sleep and thus sleep education is a potential solution to address sleep disorders. Some studies show that psycho-education programs are an effective means in helping the clinical insomnia population (Morin et al., 1994; Murtagh & Greenwood, 1995). Sleep education can increase the level of knowledge about sleep hygiene, sleep patterns, and other related issues.

Sleep education is in its infancy stage. In 2012, a study (Blunden et al., 2012) identified 12 programs in sleep education. Another research designed to assess the prevalence of sleep education in 409 medical schools reported that the average amount of time spent on sleep education in these medical schools is less than 2.5 hours (Mindell et al., 2011). The theoretical underpinning of sleep education is also to be developed.

Additionally, the consistent efficacy of sleep education remains highly complex. The most salient progress observed among all programs was the increase of knowledge about sleep hygiene. The overall sleep parameters across studies had little changes, however. Only 2 studies reported specific improvement in sleep duration. The Sleep Smart program found that adolescents in the intervention group reported more regular sleep-wake patterns during weekdays and weekends after sleep education (Rossi, 2002). In short, sleep education programs for youth improved their knowledge about sleep, while there is less consistent improvement in sleep duration or sleep hygiene. Other findings indicated that good sleep hygiene knowledge is weakly associated with good sleep hygiene practice (Brown et al., 2002). This may partly explain why sleep education program cannot contribute much to good sleep behavior and sleep quality.

Sleep education in Hong Kong is thus in its earliest stage. Only one program on sleep education for Hong Kong adolescent students has been identified. This program, conducted by a team of academics and students in universities in Hong Kong, aims to increase sleep knowledge and promote good sleep practice among school-aged children and teenagers. Twelve primary school and fourteen secondary school students took part in the program. The intervention group which contained 14 randomized schools had seminars, workshops, slogan and painting competitions, and other activities during the three months of the sleep education program. More than 400 workshops and 40 seminars taught by specialists and trained research assistants were held during the campaign. Their topics varied from factors of sleep loss to time and stress management skills. This program also provided teachers and parents with a seminar on sleep knowledge. The outcomes demonstrated that the program was effective in increasing sleep knowledge and improved, at least in short term, adolescent behaviors, psychological health and healthy lifestyle practices. However, it did not clearly achieve its second goal, that is, to change sleep practice.

A few challenges were discussed by the program team. First, before launching this program, all primary and secondary schools in Hong Kong were invited, but most school principals found it difficult to add additional lessons to school and teachers’ schedules. In the end, only 26 schools participated in the project. Second, only 10% of parents attended the seminar designed and provided to them. This indicates that most schools and parents lack awareness of the importance of sleep and sleep education for their children, and prioritize their children’s schoolwork and other activities over sleep health (Chan, 2016).

5. Recommendations for Sleep Education in Hong Kong

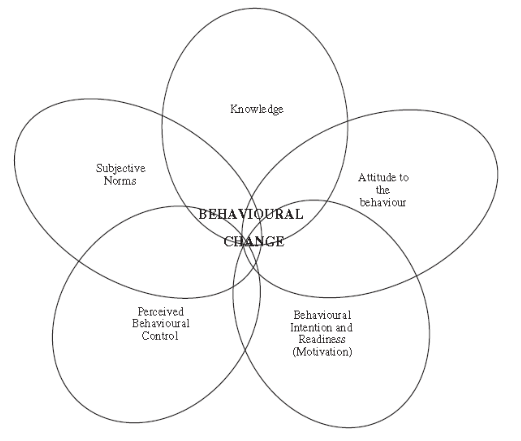

Researchers have noted that the outcomes of sleep education are not ideal. There is an increase of knowledge level but no change in sleep parameters. One of the issues identified is that there is no theoretical foundation for such educational programs (Blunden et al., 2012). Blunden et al. (2012) constructed an integrated model of behavior change (see Figure 2). Along with knowledge, motivation is suggested as the very first step before planning a strategy (Azjen, 2002). Apart from knowledge attainment and motivation, however, participants’ attitudes to their behaviors and their subjective norms contribute to behavioral change. For example, whether an adolescent decides to change his/her sleep hygiene practice would depend on his/her understanding of the effects of the behavior, attitude to the current behavior, intent and motivation to change, and the consideration of its importance and his/her readiness to change it.

Figure 2 Representation of an integrated model of behavior change (Adapted from Azjen)

Additionally, sleep disorders are not only a problem related to adolescents, but should be prioritized by parents, school teachers, and friends. It is suggested that an informal alliance among students, schools, and parents should be built to achieve greater understanding and results. The Committee of Home-School Co-operation (CHSC) in Hong Kong could play a vital role in blending sleep education in forums, dialogues and other activities. Furthermore, a communicative and mutual-supervisory relationship could be built among adolescent students so that students are able to change their sleep-related behavior under peer motivation and pressure.

Likewise, the government should not be absent in the promotion of sleep education. As mentioned earlier, a heavy academic burden is one of the most significant factors that leads to sleep deprivation. Therefore, the government could set out guidelines to adjust curriculum and assignments to improve the situation. On the other hand, sleep education can also be included into the hidden curriculum, e.g., with rearrangement of the school timetable, organizing sleep education related activities, and providing extracurricular books about sleep health, etc. Other strategies to increase and enhance sleep education need to be explored by different stakeholders.

6. Conclusion

In consideration of the close association of sleep problems and mental illness among adolescents, more attention to sleep quality in adolescents should be granted. Many Hong Kong youth face serious sleep problems, due to academic pressure and other factors. Education, which is usually considered as one of the solutions to address many sustainable developmental issues, can provide more knowledge to adolescent students and help youth obtain better sleep in a short period. However, existing studies have shown that sleep education programs thus far have brought less than consistent success in relation to enhancing sleep behavior and sleep duration. The effect of sleep education in youth is still complicated in many ways. Based on the integrated model of behavior change theory, elements for changing adolescent sleep behavior can be proposed and implemented with the cooperation and support of schools, parents and students.

7. References

Adrien, J. (2002). Neurobiological Bases for the Relation between Sleep and Depression. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6, 341–351. Doi:10.1053/smrv.2001.020

Ajzen I, Saunders J, Davis LE, & Williams T. (2002). The Decision of African American Students to Complete High School: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology; 94(810e9). Doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.94.4.810

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2014). International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3). Darien: Illinois.

Bjorkman, S. M. (2007). Relationships among Academic Stress, Social Support, and Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior in Adolescence. Northern Illinois University.

Blunden, S. L., Chapman, J., & Rigney, G. A. (2012). Are Sleep Education Programs Successful? The Case for Improved and Consistent Research Efforts. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(4), 355-370. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.08.002

Breslau, N., Roth, T., Rosenthal, L., & Andreski, P. (1996). Sleep Disturbance and Psychiatric Disorders: A Longitudinal Epidemiological Study of Young Adults. Biological Psychiatry, 39, 411–418.

Brown FC, Buboltz WC, Jr, & Soper B. (2002). Relationship of Sleep Hygiene Awareness, Sleep Hygiene Practices, and Sleep Quality in University Students. Behavior Medicine, 28, 33–38.

Chan, D. W. (1997). Depressive Symptoms and Perceived Competence among Chinese Secondary School Students in Hong Kong. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(3), 303-319. Doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-0004-4

Chan, N. Y., Lam, S. P., Zhang, J., Yu, M. W. M., Li, S. X., Li, A. M., & Wing, Y. K. (2016). Sleep Education in Hong Kong. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 14(1), 21-25. Doi 10.1007/s41105-015-0008-8

Chung, K.F. & Cheung, M.M. (2008). Sleep-wake Patterns and Sleep Disturbance among Hong Kong Chinese Adolescents. Sleep, 31(2):185-194.

Kaplan, D. S., Liu, R. X., & Kaplan, H. B. (2005). School Related Stress in Early Adolescence and Academic Performance Three Years Later: The Conditional Influence of Self-expectations. Social Psychology of Education, 8(1), 3-17. Doi: 10.1007/s11218-004-3129-5

Kliegman, R. M., Behrman, R. E., Jenson, H. B., & Stanton, B. M. (2007). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Mak K-K, Lee S-L, Ho S-Y, Lo W-S, & Lam T-H, (2012). Sleep and Academic Performance in Hong Kong Adolescents. Journal of School Health, 82, 522-527. Doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012. 00732.x

Mindell, J. A., Bartle, A., Wahab, N. A., Ahn, Y., Ramamurthy, M. B., Huong, H. T. D., Teng, A. (2011). Sleep Education in Medical School Curriculum: A Glimpse across Countries. Sleep Medicine, 12(9), 928-931. Doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.07.001 .

Morin, C. M., Culbert, J. P., & Schwartz, S. M. (1994). Nonpharmacological Interventions for Insomnia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(8), 1172.

Murtagh, D. R., & Greenwood, K. M. (1995). Identifying Effective Psychological Treatments for Insomnia: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(1), 79.

National Sleep Foundation (NSF). (2000). Adolescent Sleep Needs and Patterns: Research Report and Resource Guide. National Sleep Foundation.

Prochaska, J. & DiClemente, C.C. (1983) Stages and Processes of Self-change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 51(390e5).

Richdale, A. L. (1999). Sleep Problems in Autism: Prevalence, Cause, and Intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 41(01), 60-66. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749. 1999.tb00012.x

Rossi, C., Vo, O., Marco, C., & Wolfson, A. (2002). Middle School Sleep-smart Program: A Pilot Evaluation. Sleep, 25(A279).

Sing, C. & W. S. Wong (2010). Prevalence of Insomnia and its Psychosocial Correlates among College Students in Hong Kong. Journal of American college health, 59(3), 174-182.

Suen, L. K., Ellis Hon, K., & Tam, W. W. (2008). Association between Sleep Behavior and Sleep-Related Factors among University Students in Hong Kong. Chronobiology international, 25(5), 760-775. Doi: 10.1080/07420520802397186

United Nations (UN). (2016). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. High Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. New York.

8. Key Terms and Definitions

Adolescent student – a person in the 11-21 age group (Kliegman et al., 2007). It is a transitional stage when physical and psychological changes occur, bringing up self-identity and independence.

About the Author

Luo Yu

MEd, The University of Hong Kong

Email: luoyu.2017@ outlook.com